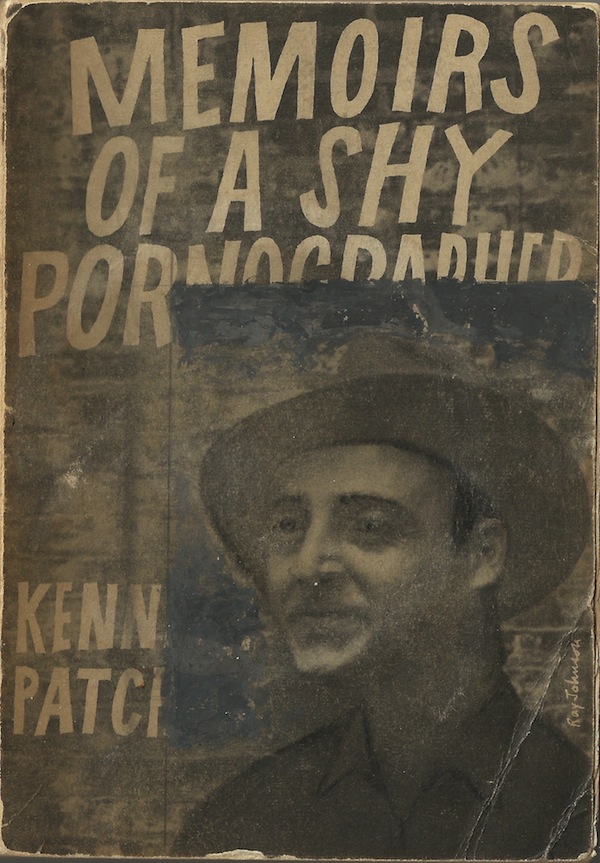

Kenneth Patchen – Memorie di un pornografo timido/Traduzione di Mariangela Venezia

DA DOVE VENGO

Caro amico sconosciuto

Mi chiamo Budd. Sono nato a Bivalve, New Jersey, il 15 marzo 1905. A diciannove anni sono andato a lavorare in una fabbrica al 640-1 di Gastor Street, vicino a Welman Dinker’s Square, a Manhattan, New York, e ho continuato a lavorarci stabilmente fino al secondo giovedi dello scorso ottobre. Mia sorella, Mabelle Frances, ha due figli, una ragazzina di dieci anni, Karlanne, e un maschio di undici, Medrid. Abitiamo in un appartamento di quattro stanze all’angolo tra Visalia e Fairwood nel distretto di Brooklyn. La porta d’ingresso dà su Fairwood.

Mabelle Frances, nata il 26 giugno 1910 a Bivalve – ma non nella stessa casa dove sono nato io – ha i capelli rossicci, intrecciati in una crocchia più grande e due più piccole, occhi marrone chiaro, caviglie grosse e pesa 108 libbre.

Medrid ha una cicatrice che va dal sopracciglio sinistro fin quasi al mento sfuggente – mani grassocce e pesa 147 libbre e mezzo.

Karlanne è piuttosto bassa per la sua età, non va d’accordo con nessuno della famiglia, e ha un’amichetta odiosa che si chiama Michael e porta varie spillette di campagne elettorali appuntate sul vestito.

Leroy Shalby, il marito di Mabelle Frances, un giorno è uscito di casa e non è più tornato – il 2 maggio del 1936, per l’esattezza. Leroy era andato un po’ a scuola, aveva lavorato part time in un negozio di scarpe a quattordici anni, e quando sparì lavorava regolarmente ma in un altro posto. Guadagnava circa 21 dollari e 50, 3.25 meno di me, sebbene lavorasse più ore e sei giorni alla settimana contro i miei cinque.

I nostri genitori sono morti investiti da un’auto quando avevamo tre e otto anni. Erano andati a fare compere a Millville e al ritorno, mentre andavano alla fermata dell’autobus un camion Franklin li ha schiacciati contro la porta d’acciaio di un banco dei pegni. Era poco dopo le quattro di un sabato pomeriggio. Abbiamo saputo, quando eravamo abbastanza grandi per capire, che la testa di mio padre si era aperta in due, la gamba destra amputata di netto e il petto dilaniato: nostra madre, più fortunata, riportò soprattutto ferite interne e morì cinquantacinque ore dopo senza mai perdere conoscenza.

Da bambini pensammo che era un peccato non avessero potuto esalare il loro ultimo respiro a Bivalve, lo avevano sempre desiderato.

Io e mia sorella fummo cresciuti da un certo Mr Ed Hall e sua moglie. Lui lavorava nei mulini dei dintorni e sua moglie, che veniva dalle colline del Tennessee, passava la maggior parte del tempo in casa, friggendo levee-welly cakes, e mescolando la pasta coi piedi. Era il modo migliore di farlo, diceva sempre. Mi ricordo perfettamente di lei, accovacciata su una sedia in cucina, con entrambi i piedi informi che si muovevano su e giù in una massa spessa, color fegato, che strabordava da un vecchio mastello di legno. Sono sicuro che se assaggiassi una leeve-welly adesso, quei momenti riaffiorerebbero dal mio subconscio, e vedrei di nuovo, attraverso l’occhio dei ricordi, i lunghi peli rossi che spuntavano dal naso di Mr. Hall.

Avevano quattro figli – Chalice, una femmina; Hegger, un maschio; Mildred, un‘altra femmina; e Wilhelmina, chiamata Will, che si vestiva da uomo e fumava la pipa a tredici anni. Io ero innamorato di Chelice e Hegger di Mabelle Frances.

Hegger attualmente è responsabile di zona di un’associazione politica russa a Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Chalice dai capelli d’oro annegò in un torrente il 12 marzo 1921. Eravamo nati a cinque giorni di distanza. La attaccarono alle macchine per respirare, ma non reagì. Sono passati molti anni prima che andassi di nuovo a pattinare.

Medrid e io dormivamo insieme su un divano in salotto. Kerlanne e sua madre in una camera dal lato della strada.

Dopo che Leroy se ne andò, mia sorella iniziò a fare la sarta. Lo stanzino vicino alla cucina doveva essere lo spogliatoio, ma quasi nessuno ci andava. All’epoca era molto imbarazzante. Per me.

Non mi piace pensare alla mia vita prima di scrivere Spill of Desire, o, come lo avevo intitolato all’inizio, The Spool of Destiny, ma devo dire qualcosa sulla fabbrica.

Avvolgevamo garze di lino intorno ai macchinari, fissandole a dovere con tre strati di colla. Con me lavoravano Neddy e “Budge” Shadron. Non ho mai saputo il cognome di Neddy. Passava il tempo libero a leggere tutto ciò che trovava su Anthony B. Comstok. Per un periodo chiamavamo Shadron “Big Bill” ma poi la smise di parlare del del gioco di Tilden e cominciò con quello di Donald Budge .

C’era un garzone che spostava su e giù i rocchetti di filo e ci portava le bacinelle d’acqua con cui ci toglievamo la colla dalle mani. Penso fosse brasiliano o spagnolo a causa del suo accento e dei capelli lunghi sulle orecchie che gli scendevano dalla testa rossa fin sulla schiena. Conosceva solo “quella” parola, che non posso trascrivere in un libro per famiglie come questo. Era vecchio per essere un garzone, all’incirca quarant’anni.

C’era una macchia rossastra vicino allo specchio dello spogliatoio degli uomini, a spesso, quando mi ci mettevo davanti, sembrava rimpicciolirsi e dilatarsi, come un enorme occhio che mi fissava. Un paio di volte ho pensato di parlarne a Neddy o Buddy, ma non ci fu mai l’occasiona giusta.

Sapevo cosa avrebbe detto Buchannan, e non volevo sentir pronunciare la solita parola.

Una delle cose che proprio non mi piacevano era che Medrid bevesse cosi tanta acqua prima di andare a dormire.

Una volta una ragazza mi ha fermato e mi ha detto:

“Anche tu hai paura?”

È successo di fronte a Ludmore’s Notions And Hard-to-find-Goods sull’ottava strada vicino alla ventitreesima. Stavo ammirando un grazioso angelo di vetro con le ali rosse e una tunica gialla a pois, in vetrina accanto a una tigre di legno verde e un lampionaio con un cappotto fuorimoda con grosse tasche, che nonostante la pittura scrostata nella mano destra – era perfetto per la mensola del camino.

In realtà ciò che amavo collezionare era il fango dei predellini dei furgoni. Mi appuntavo la targa e dopo averne grattato via un pezzetto, ci appiccicavo sopra un cartellino con la data e il nome dello Stato. Cosi facendo a un certo punto avevo il fango di quasi tutti gli Stati Uniti tranne South Dakota, Wyoming, Nevada e West Virginia.

Ho scoperto in quell’occasione che i camionisti sono sospettosi e persino un po’ rozzi a volte.

Considerando di aver cominciato più o meno a due anni, ho fatto 14196 colazioni, 14094 pranzi – (per un periodo ho mangiato tre carote e una mela ma non contano) e 14194 cene.

Ho viaggiato per 109200 miglia in metropolitana per andare a lavoro e tornare a casa. Ho indossato 361 paia di calzini, 46 di pantaloni, 83 di pantaloncini, 35 di scarpe, 102 magliette, 9 paia di scarpe di gomma e cinque paia di ciabatte.

Ho indossato 6 cappotti, 1 soprabito, 5 vestiti “buoni”, 34 cravatte, 6 paia di coprimaniche, 7 di elastici per calzini Paris e 2 cappelli, uno grigio scuro e uno giallo chiaro.

Ho usato 38 tubetti di dentifricio Colgate, 16 spazzolini Prophylactic, 348 lamette Herald Square, 3 rasoi Gillette de Luxe, 9 pettini, 2 spazzole Ogilvie, 1 pennello da barba Fuller, 121 bottiglie di lozione per capelli Tiger Lily, 94 di Indian Maiden (alle erbe), 48 di Wild Root, 25 di Kreml, 14 di Glovers, 246 di colluttorio Listerine, 92 di lozione per il viso Witch Hazel e 6 di collirio Murine.

Kenneth Patchen (13 dicembre, 1911 – 8 gennaio, 1972) è stato un poeta e romanziere americano. Ha sperimentato diverse forme di scrittura includendo tra le sue opere la pittura, il disegno, il jazz. Ha esercitato una notevole influenza sulla San Francisco Renaissance e la Beat generation.

WHAT I CAME FROM

Dear Unknown Friend

My name is Budd. I was born in Bivalve, New Jersey, on March 15, 1905. In my nineteenth year I went to work in a factory at 650-1 Gastor Street, near Welman Dinker’s Square, Manhattan, N.Y., where I worked in continuous employment until the second Thursday of a recent October. My sister, Mabelle Frances, has two children, a little girl ten years of age, named Karlanne, and a boy of eleven, who is called Medrid. We live in a four-room apartment at the corner of Visalia and Fairwood in the Borough od Brooklyn. Our street door is on Fairwood.

Mabelel Frances, born on June 26, 1919, also in Bivalve – but not in the same house – has reddish hair, worn in one large and two smaller buns, tan eyes, rather thick ankles, and weighs 108 pounds.

Medrid has a scar running form just over his left eyebrow down almost to his weak chin – fattish hands, weight 147 ½.

Karlanne is fairly small for her age, favours no one in the family, and has a nasty little playmate with the name Michael who has campaign buttons pinned all over her dress.

Leroy Shelby, Mabelle Frances’ husband, walked out of the house one day and never came back. Eight years ago – May 2 1936 , to be exact. Leroy had little formal education, going on part-time in a shoestore at fourteen, and when he disappeared he was on regular but a a different location. He was then making 21.50 – 3.25 less than I made though his hours were longer and mine only a five a day to his six.

Our parents were fatally injured by an automobile when we were three and eight. They ahd been shopping in Millville and were on their way back to the jitney- stop when an air-cooled Franklin of that period pinned them against the steel window-guard of a pawnshop. It was a little after four on a Saturday afternoon. We learned when we were old enough to understand that our father’s head was smashed in two, his right leg torn off at the hip, and most of his chest ripped out; mother, more fortunate, had her trouble mainly inside, dying fifty-six hours later without losing consciousness.

One thing we thought of a lot as children was that they hadn’t even been able to breathe their last in Bivalve, which, we knew, they would have wanted to do.

Sis and I were raised by a Mr. and a Mrs. Ed Hall. He worked in the mills around that section and his wife, a native of the Tennessee hills, spent a lot of her waking hours around the house frying levee-welly cakes, the batter for which she stirred by foot. That was the only proper way to do it, suh, she always said. I have vivid memories of her sitting crouched over on a chair in the kitchen, both her rather shapeless feet pumping up and down in a thick, liver coloured mass which overflowed the rim of a an old wooden tub. I am sure that if I tasted a levee-welly right now, all that time would fill my subconsciousness and I’d see again through memory’s eye the long red hairs sticking out of Mr. Hall nose.

They had four children of their own – Chalice, a girl; Hegger, a boy; Mildreen, another girl; and Wilhelmina, called Will, who wore men’s pants and smoked a pipe at thirteen. I loved Chalice, and Hegger loved Mabelle Frances.

Hegger is now district organizer of a Russian political association in Pottsville, Pa. Golden-haired Chalice drowned in a small creek on March 12, 1921. We were born five days apart. She was given respiration by artificial means, but did not respond to it. Many years passed before I went skating again.

Medrid and I slept together on a studio couch in the front room. Karlanne and her mother had their own bedroom on the street side.

When Leroy went, my sister strarted to do dress-making. The little room off the kitchen was supposed to be used for fittings, but mostly nobody bothered to. At times it was very embarassing. For me.

I don’t like to think much about my life before it happened – before I wrote Spill of Desire, or, as I called it first, The Spool of Destiny – but I should say something about the factory.

We wound linen gauze around armatures, wrapping them just right and putting three dabs of glue on each. Neddy and “Budge” Shadron worked with me. I never knew Neddy’s other name. He spent all his spare time reading everything he could get his hands on about Anthony B. Comstock. For quite a while we called Shadron “Big Bill” but then he stopped talking about Tilden’s game for Donald B’s.

We had a boy who moved the spools on and off the benches and brought around the basins of water we washed the glue off our hands with. I think he was Brazilian or Spanish because there was an accent around the word he said and his hair was worn long in front of his ears and came down over his red cape at the back. He never used more than that one word – which I can’t print in a family book of this sort. He was really an old boy, forty or so.

There was a reddish stain near the mirror in the Men’s Room, and often as Istood in front of it it seemed to get smaller and tighter – like an eye looking at me. Once or twice I wanted to tell Neddy or “Budge” about it, but somehow the right time never came up.

I knew what Buchanan, the boy, would have said if I told him – and I didn’t want that word near the eye.

One of the things I didn’t like was Medrid’s drinking so much water just at bedtime.

A girl stopped me once and said:

“Are you afraid too”?

This took place in front of Ludmore’s Notions and Hard-To-Find-Goods on 8th Avenue near 23rd Street. I was admiring a tiny glass angel with red wings and a little yellow polka-dot nightie that stood between a tiger made of green wood and a lamplighter in an old fashioned coat with big pockets with the paint chipped off his right hand – yet very nice for the mantel.

However, what I collected was the mud from the running boards of trucks. I’d look at the licence plate and after scraping off a nice piece get my tag with the date and the state’s name on it. In this way I gradually had mud from every state in the Union except S. Dakota, Wyoming, Nevada and W. Virginia.

I discovered that the drivers are inclined to be suspicius and even crude at times.

On the basis of beginning at two years old, I have eaten 14,196 breakfasts, 14,084 lunches – (four months once I tried three carrots and an apple, which hardly counts) and 14,194 suppers. I have travelled 109,200 subway miles getting to work and back. I have worn out 361 pairs of socks, 46 of pants, 83 of shorts, 35 of shoes, 102 shirts, 9 sets of rubbers, and five pairs of slippers. I have had 6 overcoats, 1 topcoat, 5 “good” suits, 34 neckties, 6 pairs of sleeve holders, 7 of Paris garters, and 2 hats, one dark grey, and one bright yellow.

I have used 83 tubes of Colgate toothpaste, 16 Prophylactic brushes, 348 Herald Square blades, 3 Gillette de Luxe safety-razors, 9 combs, 2 Ogilvie hairbrushes, 1 Fuller long Bristle, 121 bottles Tiger Lily hair tonic, 94 of Indian Maiden (herb), 48 of Wild Root, 25 of Kreml, 14 of Glovers, 246 of Listerine, 92 of witch hezel, and 6 of Murine.